In a previous essay I have explained why dating in accordance with the 37% Rule—the solution to the Secretary Problem, often touted as the optimal approach to dating—is ultimately a poor strategy. For those unfamiliar with the concept, the Secretary Problem suggests that when selecting from a series of options (like potential partners) that arrive sequentially, you should reject the first 37% of options to calibrate your standards and then select the next option that is better than all previous ones. However, as I argued previously, the assumption of the Secretary Problem are at odds with reality, requiring us to robotise ourselves, and even then chances of success are likely going to be a lot lower than promised.

Despite these limitations that essentially render the 37% Rule unusable, I believe that the Secretary Problem is an excellent thought experiment, and we can learn a lot about dating by comparing it to how people typically find a partner. In this essay I'll explore those lessons.

Exploration Versus Exploitation as a Mental Model

Life's most important decisions share the following structure: weed out the best option amongst many, committing to said option, and not looking back. Or at least this is the most prevalent societal view when it comes finding a romantic partner, approaching a career or choosing where to live.1

Your goal is to move from the exploration phase to the exploitation phase. From dating, job hopping, moving around to getting married to the love of your life, working the dream job, finding your home, and living happily ever after. Ideally saying yes to the best and no to the rest. Unless you're non-monogamous, have multiple jobs, or can afford to live in multiple places.

But getting to a place where you can say yes to the best and no to the rest is a process. Many of us don't marry their high school sweetheart or grow up being dead set on a particular career. As a result people vary in where they are on different timelines in the different domains of life. Your buddy might be getting married, while you've been single for quite some time. Your sister might hate her job, while you're in disbelief that you get paid for what you do. You might want to move back to the town you grew up in while your former classmate would give anything to move away.

Exploration is more tolerated in youth since it takes people some time to figure this stuff out. But we expect people to transition into exploitation mode with age resulting in immense pressure for people who have yet to tick society's boxes.2

Societal expectations use time-based rules. "You should be married with kids by age X." However, as I wrote in my previous essay, a time-based rule is only a number-based rule in disguise. They can be linked but they don’t have to be. A time-based rule only makes sense if it's backed up by iterations. For example, when it comes to hobbies and interests, the prevailing idea is that you probably know your "passion" by the time you enter adulthood—that you have done the exploring in your childhood and adolescence. And then you commit to this passion or interest for the rest of your life. But that strongly depends on how much exploration you have done as a child. If your parents got you to try many things as kid, then you might have already identified your core interests and hobbies. If you never really explored widely in your childhood and your hobbies end up being watching Netflix, going on your phone, and hanging out with friends in adulthood, then you may still strongly benefit from exploration. Age isn’t what counts, it’s iterations. The former doesn't necessarily ensure the latter and a time-based rule only makes sense if it's propped up by numbers.

Of course thinking about exploration and exploitation won't stop people from expecting you to have things figured out by certain traditional milestones. But it can be way to remind yourself that it's your exploration time that matters—not your age.

However, I don't believe that exploration is inherently mandatory, which I will explore in the next section.

The Exploration Versus Exploitation as a Diagnosis Tool

Sometimes it's good to be selective, other times it's good to be less selective. The Secretary Problem can help us figure out when which strategy is best. I will illustrate this in the context of dating because I believe that's most interesting to people; however, this can be extended to various contexts such as figuring out where you want to live or what you want your job to be.

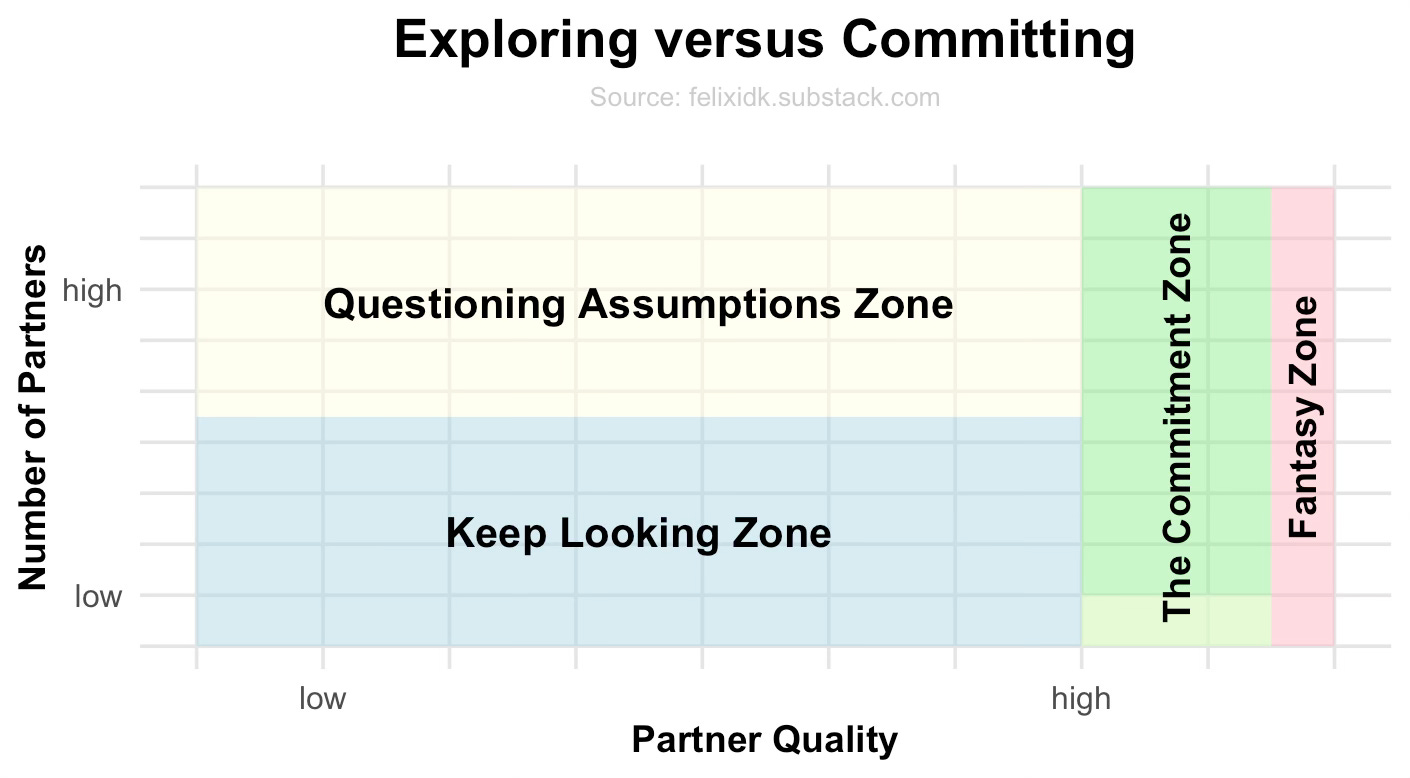

Take a look at this graph. On the y-axis we have the number of partners you have encountered, ranging from low to high. On the x-axis we have the quality of those partners you have encountered, also ranging from low to high.

Both quality and quantity are subjective. Someone's 'low' might be 10 partners while someone's 'high' could be 10 partners. Same thing goes for quality of course. Also I use the term partner loosely. How you define “partner” is also up to you. It could be relationships, situationships, former crushes, etc. However, one word of caution: it's preferable to make sure that you can draw (somewhat) fair comparisons between the partners. As I’ve said previously comparing a two-week holiday fling with a two-and-a-half year relationship is unfair.

This graph is split into four main regions, though there are no strict cut-off values. You might feel like a partner of quality 7/10 warrants commitment. Another person might think 7.2/10 is the sweet spot. You can modify the graph to your liking. I'm not here to split hairs. The aim is to simply provide you with a new perspective.

Let’s start off on the right, in ‘the commitment zone.’ Generally speaking if you encounter a great partner you should be looking to commit to them. However, there's a small area at the bottom of the commitment zone where things are a bit more nuanced. As I have stated above, I believe that exploration is not inherently mandatory. It's great if people marry their high school sweethearts and live happily ever after. These people just do a dating speed run. They do what takes some people several relationships in one. It's like landing your absolute dream job right out of college (or school). Or knowing that you'd never want to live anywhere else but where you grew up. I think this is great.

However there is a valid concern when you're in this situation and that is that if you have only ever been in one relationship you don't have a reference point. Again this isn't inherently necessary. You can have an incredible relationship without a reference point. However, you might think what you have is ‘great’ when it's not. It is more difficult to place your partner on the worst-to-best-partner scale if you have never dated someone else. You have nothing to compare against. If you are in a ‘great’ relationship with your first partner it's important that you have a realistic assessment of your relationship (easier said than done). It's important to consider feedback from people who have your best interests at heart.3

The trap to avoid in ‘the commitment zone’ is looking for ‘perfect’ when you already have ‘great.’ This is represented in red by the ‘fantasy zone.’

Perfect doesn’t exist.4 You can be incredibly happy with your relationship, but there is no 10/10 partner. There will always be some irritations. So why throw away something great in search of something else that is at best also just great? That’s a rocky road, a search with no end. You’ll never know whether there would be an even better partner there for you. This is a classic example of the inherent uncertainty of life. There’s no God that will hold up a sign saying ‘that’s the one.’ You might even already be dating the best person for you.

Now let’s move on to the remaining two zones.

First, the ‘question assumptions zone.’ Of course it’s generally a good idea to question assumptions you hold about yourself and others, this should not be limited to the ‘question assumptions’ zone. However it becomes increasingly important to do so when you have already encountered a lot of potential partners and you’ve at best felt lukewarm about them.

Here are three broad categories of assumptions that can stand in your way:

Assumptions we have about love. Maybe you have been dating great people but all of them have fallen short of picture perfect fairy tale characters hence you feel like they're not right. You're aiming higher than is realistic and as a result you don't find anyone because the person you're looking for doesn't exist.

Assumptions we have about ourselves as partners. Maybe you overestimate yourself as a partner. Maybe you think you're bringing more to the table than you actually are. Hence you are aiming too high. These people you desire reject you and the people who are interested in you, you don't give a chance. You might have to ‘work on yourself.’

Assumptions we have about our dating pool. Maybe the partners that you are looking for are not the in the places where you are searching. For example, maybe you're using Tinder but the people you're looking don't use Tinder. If you're not searching in the right spot you're going to have a tough time find a partner.

The trap to avoid in the ‘question assumptions’ zone is to not get discouraged and to avoid giving up.5

Second, we have the ‘keep looking zone.’ If you have only encountered a few partners (or potential partners) and they’re all of low to medium quality you should just keep looking. It’s too soon to tell whether your assumptions are “wrong” (although we can all do a better job at questioning our assumptions). And it would be a mistake to settle here. The trap to avoid in the ‘keep looking zone’ is to not settle for low quality partners.

A classic example that illustrates the ‘keep looking zone’ quite well is if you are in a small secondary school. Then chances are good that 1) there are not a lot of people (if any) that you are interested in romantically and 2) you’re not the only one who is interested in them. Hence high competition for the highest quality partners. And if you end up with no partner—you might feel like there’s nobody out there for you. But then when you leave school you meet a wider range of people and you end up finding people who you click with way more than your former classmates.

To get the most out of this graph I recommend drawing the graph yourself and placing some former partners on the graph to see where they fall. And as I said previously this can be easily adapted to also apply to jobs or places to live.

Our Information is Likely Less Accurate Than We Think

Generally most people don’t care much about mathematics. The only reason why we care about the Secretary Problem is that it can be applied to finding love. Many of us struggle with love. We concede that we aren’t the best at picking partners. We know that there is room for improvement. We cannot just walk into a bar and know that the third person on the right is the one.6 This essentially comes down to the issue of imperfect information. If we had better information then we could better assess potential partners but the problem is that it’s not always obvious what information is good and what is bad.

When it comes to hiring, managers typically swear by the unstructured interview. They sit across from the candidate. Using their expertise, experience, and understanding of people to “skilfully” extract a judgment of the candidate, leading them to confidently prophesise how this person would fare as a secretary.

We’ve known for decades that unstructured interviews are pretty garbage at predicting future job outcomes and yet they remain widely used. People willingly cling onto poor information.

I don’t have any proof of this, but I suspect many of us face the same issue when dating. We swear by information that is actually not very indicative of partner quality. Theoretically if we had better information, if we had a more accurate view of dating as a whole and the potential partners we encounter, we could make more accurate decisions about who or who not to date.

The most basic version of the Secretary Problem assumes that you are a blank slate, that you gain your information in the exploration phase. A phase that begins when one seeks out a partner and ends when one has seen 37% of one’s respective dating pool.

However by the time we start dating, we have already accumulated a significant amount of information on love and relationships. Likely most influentially we have seen our parents’ relationship. We have seen other relationships around us (our friends’ parents, neighbours etc.). We’ve heard stories. We’ve seen movies. Even while dating, we keep gathering data. We scroll social media. We hear stories from our friends. We see things on TV. But how helpful is the information we have internalised really?

As I have written about previously, the most vivid information is typically also the information that is least helpful to us. And it is precisely this kind of information that leads us to conflate populations. Population conflation occurs when you falsely try to generalise from a sample of one population to another distinct population. In other words, comparing apples to oranges.

For example, you watch a Disney movie or a romcom and you unconsciously pick up on some of the lessons from the movie. And then you get frustrated with your partner because in the movies prince charming is so thoughtful. You’d bet Prince Charming would never have to be asked to take out the rubbish. In fact prince charming never has to bring out the rubbish because 99% of the story focuses on the pursuit and at the end up the movie they simply lived happily ever after.

It of course makes little sense to conflate a fictitious couple from a movie with your very real relationship, we know that. But yet we fall into this kind of trap all the time.

Social media is also fertile ground for population conflation. Most teenagers today grow up with social media where they are bombarded with curated snippets from the idealised love lives of others. We all readily say that social media is fake and staged. Yet we still catch ourselves longing for these unrealistic moments. Or unrealistic partners. So we end up comparing our lives to illusions.

Social media and the news are pretty catastrophic ways of estimating base rates—the percentage of people (in a population) who have a certain quality—because we are more likely to see and hear about the extremes. The average is most often uninteresting. It’s the extremes that stand out. While the average goes unnoticed.7 This is the stuff that we have to imagine. But when you see something, it’s very difficult to imagine something that isn’t there. For example, the argument a couple had right after taking a picture perfect selfie.

This is the issue of survivorship bias. You only see the content that makes it to social media. There are 86,400 seconds in a day. We forget all the photos that could have been taken but weren’t. We forget all the people that our algorithm filters out, or that don’t even post on social media. In movies you only see the scenes someone thought were worth writing. If the entire movie was full of average day-to-day scenes it would be boring.

Our timelines are overrepresented with the extreme. For example, with young, attractive, and rich people. These are the people we want to be and be with. Therefore, they end up on our timelines because these people capture our attention. Since our timelines are overrepresented with these people we get the impression that the world is abundant with these potential partners. But you are confused because you rarely come across these people in your daily life. Frustrated that you live in the wrong area.

That’s the fallacy—just because you see and hear about something all the time does not mean that it’s common.

Young, attractive, and rich people are abundant online because people from all over the planet cross your timeline. But when you walk around in day-to-day these people are a lot less common because they aren’t artificially aggregated. There’s no endless supply.

Or another example, your average person does not openly discuss their dating experiences on the Internet. So the dating stories you hear on the internet are not representative of most peoples’ romantic lives. An average dating story on the Internet is also not likely to go viral. Therefore, you are likely to be exposed to the most extreme takes.

If a tiny percentage of a large group of people does something, that’s relatively speaking rare but in absolute terms a lot of people. And can falsely leave the impression as if this thing is a lot more common than it actually is.

This is the trap people often fall into with Only Fans. A prevalent but false sentiment that I see on social media is the idea that these days so almost all women do Only Fans. The reason people why people tend to overestimate the amount of people doing Only Fans is because you are disproportionately likely to encounter these people online because sex sells.

Let’s do a very rough calculation. There seem to be approximately 3.5 million Only Fans creators worldwide and 1.1 million in the US alone.8 Those are big numbers but let’s stick with the US as an example. Assuming that all these 1.1 million US Only Fans creators are female adult-content creators (which they aren’t). In 2023 there were approximately 101 million women between ages 18-64 living in this US.9 So the 1.1 US Only Fans creators is actually only 1% of US women between ages 18-64. Of course Only Fans is likely to be more popular among younger women than older women and Only Fans is going to be more popular in certain parts of the country than others, but it still comes down to the same conclusion—only a tiny percentage of American women are Only Fans creators. You can discuss the morality of Only Fans and how many women are gravitating to the platform, but the claim that nearly all women are doing Only Fans is categorically false.

Accessing accurate information about the world we live in is more difficult than most people think. I’ve discussed at length what information I believe sucks. Now it’s time to discuss information that I think is pretty good.

Friends of the Opposite Gender

One pretty reliable way of getting quite accurate information without actually dating is through being friends with people are of the gender that you are attracted to.

I’m not advocating for people to pretend to be friends with people in the hopes of it turning into more. The motivation should purely be to make a new friend, to get to know someone deeply. Of course, it can happen that you fall for a friend, but this should not be the reason why you initiated the friendship.

When it comes to dating, once the box of mutual attraction is ticked, you want to end up with someone that you get along with, a friend. So friendship information is super helpful. You notice qualities that you like and dislike in your friends. These might be qualities you’d search for or avoid in a partner.

I suspect that merely by attending a co-ed school you get a good sense of the distribution of potential partners assuming you interact and are friends with members of the opposite gender. Why is this important?

Well it helps with defining a range—getting reference points.

Remember the worst-to-best partner scale from my previous post? If you have opposite-gender friends or know people of the opposite-gender well then probably subconsciously have a good idea where they would theoretically fall on your worst-to-best partner scale. For example, compared to the people you know of the opposite-gender, Harry is really a horrible person. While John is kinder than the average guy you know. This is important information that helps when dating because it helps you decide whether you should commit or keep exploring.

In conclusion, the Secretary Problem is a pretty shitty strategy for dating, but by understanding the balance between exploration and exploitation (commitment) and gathering better information, we can make more thoughtful choices about when to keep looking and when to commit. The goal shouldn’t be to find a mathematically perfect partner—that’s impossible. The goal should be to find someone great who you can build a fulfilling life with.

Exploration versus exploitation can of course also apply to other areas in life such as picking a restaurant to eat, e.g., should you keep going to your favourite restaurant (exploitation) or should you explore new restaurants (exploration).

When it comes to dating, ideally your first love is “the one,” however, since that rarely works for most people, the view seems to be that in general you date several people in your teens and early twenties, and then you end up getting married in your late twenties or early thirties. When it comes to a job it’s also unlikely that you hit the jackpot first try, so switching jobs is deemed normal in the beginning of your career. However, the expectation is that with time you cultivate your taste and figure out what you like.

For example, if none of your closest friends and family members like your partner and it’s for a reason you would also not like a partner of a loved one, it’s not a good sign.

There will never be a person that you will be perfectly aligned with on everything. Let’s say there are a hundred ways in which partners can meaningfully differ and each way can range from 1-10. That means there are 10^100 (a one followed by 100 zeros) possible combinations—making it mathematically impossible that there is a person for everyone that is perfectly aligned. The good thing is that not all ways in which you can differ are equally important. Think 80/20. It’s important that you are closely aligned on your core values and broadly on a handful of the big issues. The difficult part is figuring out what the important things are. But once you have a great relationships there’s no real way of going beyond that. There will always be some annoyances or misalignments.

Two more things: These are three examples categories but there are likely more. And a pretty solid way of questioning assumptions is figuring out what some of your assumptions are. For example, “I will find a great partner on Tinder.” And then asking ‘why’ a bunch.

Some people claim that this happened to them and that they have now been happily married for 27 years. There are two things to keep in mind. Survivorship bias: We rarely hear about the people who that feel like someone is the one and then it doesn’t work out. Luck: Just because it has worked for someone doesn’t mean it’s a reliable path for everyone. Just because Jeremy won the lottery doesn’t mean you will.

For most people a pretty good rule of thumb for estimating the frequencies of certain qualities in your dating pool is to think back to your class from school. E.g., “What percentage of the guys were a taller than 6.2?”