One of the biggest struggles I had when transitioning into university was being asked to give my opinion. This didn’t really happen to me in the first 18 years of my life. And if it did it was usually about very subjective things like “What did you think of Sylvia Plath’s Elm” or “Do you think it is acceptable to depict Hitler in a movie?” I had no problem piecing together opinions for stuff like that. But I was never really asked to give opinions aimed at reality. Nobody asked us to give our opinion on the Theory of Continental Drift or on Mendel’s pea plant experiments. So, when in university I was asked to give opinions on psychological theories, on how things are actually supposed to work, I struggled. All I kept thinking to myself was: “how am I supposed to give an opinion on this if even the experts are still duelling it out?”

In school we mainly absorbed information. No questions asked. It was implied that the information we were learning was the correct kind of information. It never actually occurred to me that I might be learning something inaccurate. Critical thinking never really crossed my mind back then. This changed when I went to university. Suddenly I was supposed to assess the quality of scientific journal articles. We were expected to actually think about what we were learning.

Critical thinking is one of those things where everyone says it’s important, but almost nobody does it. People think they care about the quality of their beliefs, but in reality many people don’t. Lecturers would voice the importance of critical thinking while putting bloated definitions of critical thinking on their slides.1 Thinking critically seemed to be a learning outcome for almost every university course I took. I even took a course called Critical Thinking (one of the best courses I ever took).

Despite this, I felt like I was rarely surrounded by students who thought critically. From first-year undergraduate courses to PhD-level courses, people seemed to revert to what they knew from school, blindly accepting what the authority figure said. Even outside of class, when talking about politics or other societal matters, it was usually a pre-chewed take from someone else. Maybe people have reflected and critical takes, but I am under the impression that I rarely hear them. Usually you can ask people “why” once or twice and they stumble. But I can’t blame them, I’d stumble too. I probably hold less than 5 reflected opinions, 99% of the time I say things I heard someone else say.

Critical thinking is highly sought after—it’s free, and yet it’s so rare. Why?

When something is highly sought after, free, and rare, it’s probably difficult and involves a lot of effort. Otherwise we’d all have six packs and toned glutes.

We have limited time and there are a near infinite amount of topics that we can have opinions on. Forming well-rounded opinions takes time. Therefore, we cannot form well-rounded opinions on everything. On top of that, it can be deeply uncomfortable to question something that’s foundational to our world-view. And even if we go through the lengths to form an opinion, we cannot bank on the fact that our take will remain “bulletproof” till the end of time.2 In the same way that it’s easier to skip the gym, it’s easier to just regurgitate someone else’s opinions.

What Even is Critical Thinking?

A huge barrier to critical thinking for me was that for a long time I just didn’t know what it was. I knew what “critical” and “thinking” meant. I knew it was something I didn’t do. I knew it was something I wanted to do more of. I knew what the bloated definitions meant. But I didn’t know how to do it. I didn’t know how to get from the noun to the verb. Critical thinking felt like a mysterious thing only really smart people did.

This problem instantly dissolved when I described this frustration to my professor who simply replied that to think critically is to question things. This blew my mind. Judging by this definition I was already thinking critically to a degree since I was no stranger to asking questions.

I thought that the only outcome of asking questions was understanding. But now I believe that asking questions is also closely related to critical thinking.

If you are trying to understand something you’ll get confused at some stage and in order to resolve your confusion you ask questions. If you still don’t understand you might bemoan that your teacher is bad at explaining things. Or you might blame yourself for being “too stupid to understand.” But there’s also a third option. Maybe what you are being taught doesn’t actually make sense. In school I never even considered that this was an option.3

Critical thinking requires to not instantly dismiss confusion by thinking that you’re “too stupid to understand” and considering that “maybe what I’m being told doesn’t add up.” This is a tough one to balance because you don’t want to be the person that starts questioning something that absolutely does make sense but is embarrassingly unaware.

When I was in the beginning of my bachelor’s they tried to explain the scientific publishing system to us. At the time I kept thinking to myself “surely I’m missing something here, this makes no sense.” But over the years I have come to realise that the system in fact doesn’t make sense. Many professors acknowledge this (at least in private). But when I was struggling to understand the geometry of the circle in secondary school it would have been foolish to dismiss the concept and say “this doesn’t add up” because I just didn’t care for geometry.

If something doesn’t make sense to you it’s important to consider these three sources of confusion. Does it make sense but I just don’t understand it yet? Does it make sense but someone is doing a poor job at explaining it? Or does it actually not make sense? As a rule of thumb, it usually takes time and effort to rule out the first two options.

Ditching The Expert

One of the core concepts that has been shaping my understanding of critical thinking has been Nullius in Verba. Nullius in Verba is the motto of the Royal Society, the UK’s national academy of sciences, and it means to take nobody’s word for it. When it was chosen in 1662, it was meant as a reminder to “withstand the domination of authority and to verify all statements by an appeal to facts determined by experiment.”4 For example the theories of Aristotle went largely unquestioned for hundreds of years. This was a stance against the idea of “well this is true because some geezer 2000 years ago said so.” Which sounds obvious when you put it that way, but it’s an easy trap to fall into. One time I was reading a collection of Voltaire’s quotes and I was thinking to myself “wow this is all so true, this guy gets it,” until I ended up reading: "Fools admire everything in an author of reputation."

I chuckled. I was being exactly this fool. It felt like this line from the 1700s was meant precisely for me in that moment. This is the trap that I was stuck in the beginning of college. I put “authors of reputation” on a pedestal. I didn’t think I was able to question these people. I was just some 18 year old schmuck and they were the likes of Voltaire and key figures in the field of Psychology.

When I started reading, I believed everything that an author would write. Daniel Kahneman is the figure in decision-making research and a Nobel laureate so everything he wrote in Thinking, Fast and Slow must be right. Susan Cain wrote the book on introversion so everything she writes about it must be correct. Seneca is respected by many people so surely everything he says is true.

Authors are very knowledgeable on their subject matter, but that doesn’t mean that they automatically get everything right. And this makes sense because experts disagree.5 If two experts disagree they can’t both be right. This is something I didn’t really consider at the time. Instead I tried salvaging the expert opinion. What do you do if two experts disagree? Well, then you just pick your preferred expert. The one that looks like you, talks like you, thinks like you, is in your bubble, has more prestige, etc. What if two of your preferred experts disagree? What do you do then? I didn’t think that far back then, but at some stage you run out of biases and heuristics and you have to start thinking for yourself.

In 2018 a documentary called The Game Changers came out. It questioned whether you needed to eat meat in order to achieve peak performance as an athlete. I remember watching some clips of an episode of The Joe Rogan Experience where a producer of the documentary was debating some “globally recognized leader in the fields of ancestral health, Paleo nutrition, and functional and integrative medicine.”6

(At the time I wasn’t aware of the credentials of either.)

I remember watching the clips and feeling so conflicted. Two experts in the field of nutrition strongly disagreeing. Who do I root for? If both are world renowned experts then how do I choose between them? What should I even believe at this stage?

I thought by yielding to the experts I was doing the right thing. “Of course someone else is going to be more knowledgeable on the topic so their opinions will be more valid.” By bowing in front of the giants I thought I was taking a stance of humility. But where does this “humility” come from? Children are naturally great at asking questions. They question everything. But we are uncomfortable with the fact that we do not know the answers to some of their questions. So we end their line of questioning forcefully with statements like “because I said so.” And so the appeal of authority is born. It’s easier for the parent to raise a child if the child thinks that the parent has answers (even if it’s “because I said so”). At some stage we know that our parents don’t have the answers to everything. But we still crave this certainty so we presume the experts have all the answers. Then we learn that the experts also don’t have the answers and that everyone is just winging it.

So in the end we’re yielding to experts who are also just winging it and who are in fierce debates amongst each other. Nobody has the answers. So, reflexively taking someone else’s answers is actually a bad thing. I was renouncing all my responsibility and disguising it as a good thing. I thought I was being humble when I was being meek. Taking this approach means that you cannot possibly have any beliefs because there will always be someone with a more well-rounded opinion. I used to think that there was a trade-off between humility and questioning an authority. Today I believe that nobody is above questioning. Not Aristotle, not Darwin, not your favourite expert. That doesn’t mean that we always have to question everyone, but more that just because a person of authority says something, it doesn’t mean it’s automatically correct. Importantly, just because we shouldn’t automatically believe someone because they’re experts also doesn’t mean that experts are automatically wrong about everything.

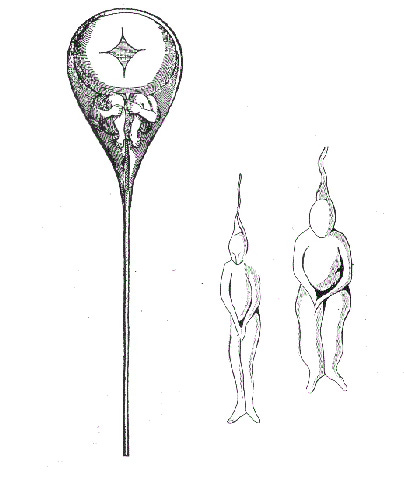

The way we progress is by questioning things, especially the things that we deem so foundational. It’s easy to forget that the things that were once the state of the art are now the laughing stock. People used to think that we originated from miniature versions of ourselves that were chilling inside sperm cells.

We have progressed just because someone had the courage to question it. We love authority figures because they make things easier for us. We can use them as a heuristic and we won’t look like idiots if expert advice fails. You might not have the knowledge that experts have. But you are still free to question their assumptions. Importantly, you are however not owed to be taken seriously.

It’s also perfectly fine to regurgitate an expert’s opinion as long as you are transparent about it and keep in mind the limitations. This goes back to the idea that we cannot possibly have our own opinions on everything. Some things are just difficult to have opinions on. I am reminded by this every time I go to the dentist. If my dentist says that I need an X-ray for an additional fee, I’m not really in a good position to assess that statement. My girlfriend once went to two different dentists over a year with the first saying that she had a cavity and the second one saying she didn’t. What are you supposed to do in a situation like that? Ask a third dentist to split the tie?!

But there are also so many things that I don’t care about or know anything about. I am unlikely to ever be able to take a stance on a disagreement between two quantum physicists. I don’t care about quantum physics. I have zero urge to learn about it and am completely ignorant to all things quantum physics. I don’t even know what it is. I will never have a well-rounded independent opinion on quantum physics. And that’s okay.

Taking it Too Far

I think ‘take nobody’s word for it’ is good advice. It’s good to not just believe something just because an authority figure said it. It’s good to base your beliefs on information that you have thought through yourself.

Nullius in verba is a good principle, but I’ve struggled with taking it too far. There were times where I’ve taken it to mean ‘take nobody’s word for anything,’ which is practically impossible and paralysing. For example, if I read a scientific journal article I have to take the author’s word for some of it. Yes, I can be sceptical of results, methods, and statistics, but at the end of the day the only way to not take someone’s word for any of it is by replicating a study yourself. Even then, it’s turtles all the way down because studies are based on prior studies and assumptions. So, this would imply that you cannot gain any knowledge from a source that you haven’t fully verified yourself. If taken literally, progress would come to a screeching halt.

It’s impossible not to be influenced by the thoughts of others. Even thinkers that are hailed as making unique contributions based their ideas on the work of others. Completely independent and original thought is impossible. We do not live in a vacuum. I think it is good to be aware of this and to accept it. But that doesn’t stop you from asking questions and coming to different conclusions.

How to Get Started?

I struggled a lot with critical thinking because I didn’t know where to start. If someone asked me where I would start if I had to figure it out again it would boil down to two simple but difficult things: asking questions and writing.

I believe the key to critical thinking is asking questions. What questions? It depends. If someone makes a strong claim about something like “we originate from miniature versions of ourselves that were chilling inside sperm cells.” You might ask: “What is your evidence for this?” Or less aggressively: “fascinating! Where did you hear of this?” Then you can evaluate their response and see whether that meets your threshold for reliable information.

One of my favourites is asking “why” a bunch. This is what I mainly use for questioning my own assumptions. For example, “I think it is important that strangers don’t have a negative opinion of me,” followed by whys until I cannot ask why anymore. This will help me understand the root of my assumption.

I think what threw me off for a long-time is that the thinking part in critical thinking seemed as if it were an invisible and abstract process. But for me it’s not. When I think “critically” it involves words. It could be speech-to-text or writing. It’s not generally something I do in my head while staring off into the distance.

I thought that once I’d finally overcome the struggle of not knowing what critical thinking is I’d turn into a critical thinking legend. But of course that wasn’t the case. There are still many other barriers as I’ve mentioned earlier. It’s also important to realise that you’re not either a critical thinker or a non-critical thinker. It’s not that black and white. Nobody can think critically all the time. That would be strenuous and time inefficient. It’s all about thinking critically more often about the things that matter.

I mean definitions like this one: “Critical thinking is the intellectually disciplined process of actively and skillfully conceptualizing, applying, analyzing, synthesizing, and/or evaluating information gathered from, or generated by, observation, experience, reflection, reasoning, or communication, as a guide to belief and action.”

“When the facts change, I change my mind. What do you do, sir?”

In retrospect I do think that in school it was mostly the first two options. The vast majority of things made sense. I just wasn’t motivated enough to understand things and occasionally I had poor teachers.

https://royalsociety.org/about-us/who-we-are/history/

I use the term “expert” very loosely.

I enjoyed reading this! A good reminder to trust yourself as well as others ... balance :)

Great article again. What do you think of using expert consensus as a guide to beliefs? As you say, you can't fully and responsibly critically think everything, since you don't have the time and energy.

I'm not an expert on climate change but given the strong expert consensus that a substantial portion of warming is due to human activity, I accept that conclusion. I'm not an expert on vaccination, but given the strong expert consensus on how well they work, I accept that conclusion. I'm not an expert in biology, but given the strong expert consensus that evolution explains the origin of species, I accept that conclusion. Etc. I always want to take a cursory glance at WHY a particular position is the expert consensus (i.e. what evidence they're relying on), but in the end, some trust in the experts is inevitable.

Where you draw the line for "strong expert consensus" is debatable but I feel like some acceptance of the principle above is important for avoiding a complete rejection of valuable institutions and emboldening of crazy internet people.